I’ve been thinking over the last days of how to describe the differences between digital living in the US and Sweden, as an American spending quite a bit of time in the north. Are there differences?

The more I think, the more I feel that there are more similarities than differences, that some cultural differences aside (largely related to Sweden’s stronger public safety net and related expectations), daily life in Sweden is swept up in many of the same patterns as shape digital life in the U.S. today.

Daily Life Abroad

On a personal level, Internet access allows me to stay much more connected to the US when I’m in Sweden than otherwise. I can continue to work “there” (the US) even when I’m here (Sweden). My colleagues are largely the same, as is my day-to-day work. In New York, as in Sweden, I spend a large part of my working day at my laptop, sipping cups of tea, reading and writing.

I can still access and participate in the US internet landscape even when I’m not physically in the US. This sounds mundane, but it’s actually pretty amazing when one stops to consider the implications. And, I indeed continue to participate much more in the US-online-world than I do in the Swedish one. With a VOIP phone I can even keep my NYC office number, easily calling the US or receiving calls. And, with a six-hour time difference working cross-continentally with the east coast US feels relatively reasonable (3pm in Sweden = 9am in NYC). Even when I’m in the US, many of my work relationships are mediated by technology, as collaborators and clients often live in other US cities, sometimes on the other side of the country.

To put things in perspective, I think about the story a friend told me about her time in China. As a young student at Yale in the 1970s she got the opportunity to study in Beijing just after the Cultural Revolution, at a time when the country was generally quite closed to foreigners. At Beijing University (often considered China’s equivalent Harvard) there was a small reading room with foreign newspapers such as the New York Times and The Washington Post. The room was off-limits to Chinese students, but foreign students and a handful of scholars were allowed access. The newspapers were often at least a week old, given the transport time involved. But, my friend would read the news, now and then, to get a sense of what was happening in the world and at home in North America. After two years in Beijing, surrounded by Chinese language and culture with only slow and occasional access to “home”, returning to the West was a shock.

Shared Language, Shared Culture

My friend’s experience abroad in 1970s China is certainly very different from my experience of living in Sweden today (I also spent stretches of time in China in 2004/2005/2006, but that’s a different story!) Here, many instantaneous lines of connection remain open for me with the US. And, there are many similarities between New York and Stockholm life — or, perhaps, better said, many Swedes and Americans participate in a shared international culture of iPhones, well-roasted coffees, hip secondhand shops, the Millennium trilogy of Stig Larsson books, big theater showings of the Hobbit, American TV shows, and Swedish bands ranging from ABBA to First Aid Kit.

Part of this crossover is related to the fact that a large majority of Swedes speak and read English very well. Bookstores and libraries in Stockholm typically have a large selection of English language books, Swedish academics often publish in English, and some workplaces are entirely English-speaking. Despite the fact that English is not one of Sweden’s official minority languages, government websites and services are often offered in both Swedish and English. All of this is not for the benefit of native English speakers alone, but rather allows Sweden to connect with a large international community with English as a lingua franca.

In digital culture, the overlap is often even more clear. Many computer-related words have been taken directly from English into the Swedish language. Apple devices like iPhones are incredibly popular. And, episodes of American shows like Portlandia and True Blood are available on the Swedish public television website.

Episode of Portlandia currently available on SVTplay.

The media connections continue: recently a Swedish relative began reading The Economist and The New Yorker on his tablet — as this digital option is much cheaper than an international paper subscription and makes it affordable. A woman I spoke with in a shop in Stockholm in early January had just finished gorging on a set of American science fiction novels she’d ordered on Amazon.com. Many of the books, she said, had labels from US libraries — presumably books the libraries had purged from their collections. And, a friend showed me beautiful antique quilts from the southern US that she’d won on Ebay and had shipped to Sweden.

(This digital exchange isn’t always so smooth — for instance, I can’t buy Swedish language media via my US-based iTunes account, and it’s hard, though by no means impossible, to access certain American media online from abroad.)

Non/Digital Summers

Nevertheless, there are some basic differences (and many more subtle ones — surely including those I haven’t yet discovered). Most markedly, Sweden’s social safety net with affordable day care, low-cost and high-quality healthcare, support for families with children, and long vacations has an impact on life in general, as well as on digital norms.

I’ve slowly learned, for instance, not to expect a reply if I email someone between mid-June and mid-August. A reply is possible — just not a given. During these summer months much (but not all) of Sweden is off on vacation: ideally and idyllically at a small family cabin by a lake or the ocean. Many offices shut down for at least a month, and it’s not uncommon to receive an email auto-reply informing you that the person in question won’t be back in the office for six weeks. That is, there is a social expectation, in the professional world at least, that even the digital shouldn’t be allowed to interfere with these holy summer months.

Of course, there are exceptions. And, perhaps they are becoming increasingly common. With mobile broadband more people can take the internet to even previously remote locations because, as this short article explains, service is available in 99% of inhabited locations in Sweden (note the photo of the couple using a laptop in their camping tent). Further, many parents feel increasingly pressured to bring not just their own, but their children’s digital devices on vacation.

A real life example: last summer we visited a friend and her family at their beautiful small old summer house in the countryside. She was working on finishing a book on the history of black metal (music) and explained that she was often up half or all of the night after her little girls went to sleep working on it. She could send chapters to her collaborator, she explained, via her mobile phone — which could be connected to her computer for net access.

Digital Patterns

From my own window in the Swedish countryside I can see four tall white birch trees, and behind them a gray 3G mast, just as high. Sometimes I ask myself: would I be willing to give up using a mobile phone if it meant that I didn’t have live in the shadow of its infrastructure? What’s the price of 99% mobile coverage? (In achieving the ideal of ubiquitous access Swedish telecom companies faced unexpected delays, as many citizens fought the arrival of 3G towers on or near their land. In part because mobile telephony is classified as a potential environmental hazard, local cities and towns had to consider these objections, even if, in reality, most weren’t heeded.)

While there are some differences in the build-out of telecom infrastructure in the US and Sweden, the overall patterns are remarkably similar. From the consumer side, there has been a decline in landlines in favor of mobile and VOIP telephones over the past decade in both places. Home broadband and internet use have increased markedly (see US stats here; and Swedish stats here), and now tablet use is on the rise. One interesting difference is the cost of a mobile phone service in the two countries: 4 cents per minute in Sweden versus 18 to 25 cents per minute in the US, according to a 2010 study,

Surprisingly, 1.3 million people in Sweden — about 1 in 7 people — don’t have the internet at home. This is much less than in the US, where as of April 2012 34% of adults didn’t have a home net connection, or 1 in 3 people. Still, for those who don’t have the internet at home, or don’t get online regularly, the patterns in both countries are remarkably resonant. In both the U.S. and Sweden, those under 65, who have higher levels of education, and higher incomes are much more likely to be online at home. In addition, the reasons given for not being online are similar.

Perhaps the difference in the degree of disconnectivity between the two countries is reflective of the fact that due to a long history of supportive policies, Sweden is more socio-economically equal than U.S., leading to less drastic gaps in education and income.

Video still from De Bortkopplade (“The Disconnected”)

On a cultural level, corresponding patterns are also evident. In Sweden, like the US, as increasing numbers of us become connected, more of us are experiencing internet burnout. Or, a growing sense that we can’t survive without our digital devices: not always a pleasant sensation. About 40% of Swedes, for instance, say they can’t “live a normal life” without the internet, and 7 out of 10 “can’t live” without their mobile phone.

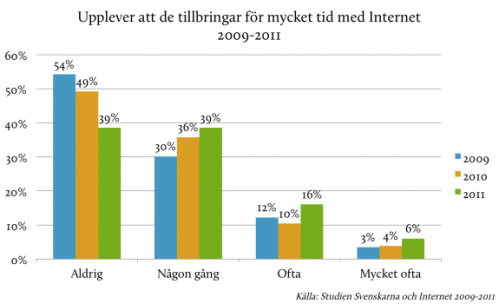

Percent of people in Sweden who “Feel that the spend too much time with the Internet, 2009-2011”, see study here. Bar graph labels, left to right: Never, Sometimes, Often, Very Often.

Still, in both countries, researchers and students at the biggest technical universities continue to study gaming and other digital futures with excitement and it’s considered to be more harmful for children to grow up without regular technology access than for them to spend too much time with devices. At the same time, over a recent lunch with a Swedish colleague, she related, with concern, how hard it can be to pull her children away from computer games and bring them outside: a situation perhaps not to unfamiliar to many parents in the US.

So, is digital living in Sweden different than in the United States? One could say that in some ways it is, but it’s perhaps more interesting to explore the surprisingly many parallels and interconnections.